The Gift of South Dakota

Subscriptions to South Dakota Magazine make great gifts!

Subscribe today — 1 year (6 issues) is just $29!

The Man Who Saved the Buffalo

|

| The buffalo that roam Custer State Park today can trace their lineage to the five calves that Fred Dupree and his ranch hands captured in 1883. Photo by Chad Coppess/S.D. Tourism. |

Many people have heard of Scotty Philip’s role in saving the buffalo: how the herd he built up on his central South Dakota ranch provided the seed stock for the majority of the buffalo being raised today. Not so many people know that if it hadn’t been for Frederick Dupree there might not have been any buffalo for Philip to save.

In a sense, I began this article years ago, when I first heard of Fred Dupree. I didn’t get far on my research until the funeral for Evie Nystrom, of Pierre, in 2003. Evie had originally come from Dupree’s country, the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation. At lunch following the funeral, I was telling the folks sitting at my table how I had tried, without success, to locate Fred’s grave.

“That’s easy,” said Kathy Fisher, one of Evie’s young nieces. “He’s buried on our ranch.” She and her husband, Darrin, work her father’s land about 30 miles south of Eagle Butte. The cemetery where Fred and most of his family are buried is a half-mile from their home.

“We have buffalo on our ranch that are probably descendants of the Dupree herd,” chimed in Karen Hump, who with her husband, Dave, raise 300 head of buffalo on their Cheyenne River Reservation ranch. Kathy and Karen are sisters. Dave is a great-grandson of Chief Hump.

With that, this old writer’s curiosity was sparked, and I was off to Grand River country.

Frederick Dupree was born in 1818 in the village of Longueuil, Quebec, on the St. Lawrence River opposite Montreal. (At various times, Frederick’s surname was spelled Dupuis, Dupree, DuPriest, Dupri and Dupree. Dupree is the spelling on his tombstone.)

As a young man he made his way to Kaskaskia, Illinois, on the Mississippi River below St. Louis. Kaskaskia was home to a large number of French-speaking settlers, like Dupree, and many of them were involved with the booming fur trade whose hub was St. Louis. Fred probably signed on as an engagee, a laborer, working on the boats and trading posts that tapped the rich fur resources of the upper Missouri basin.

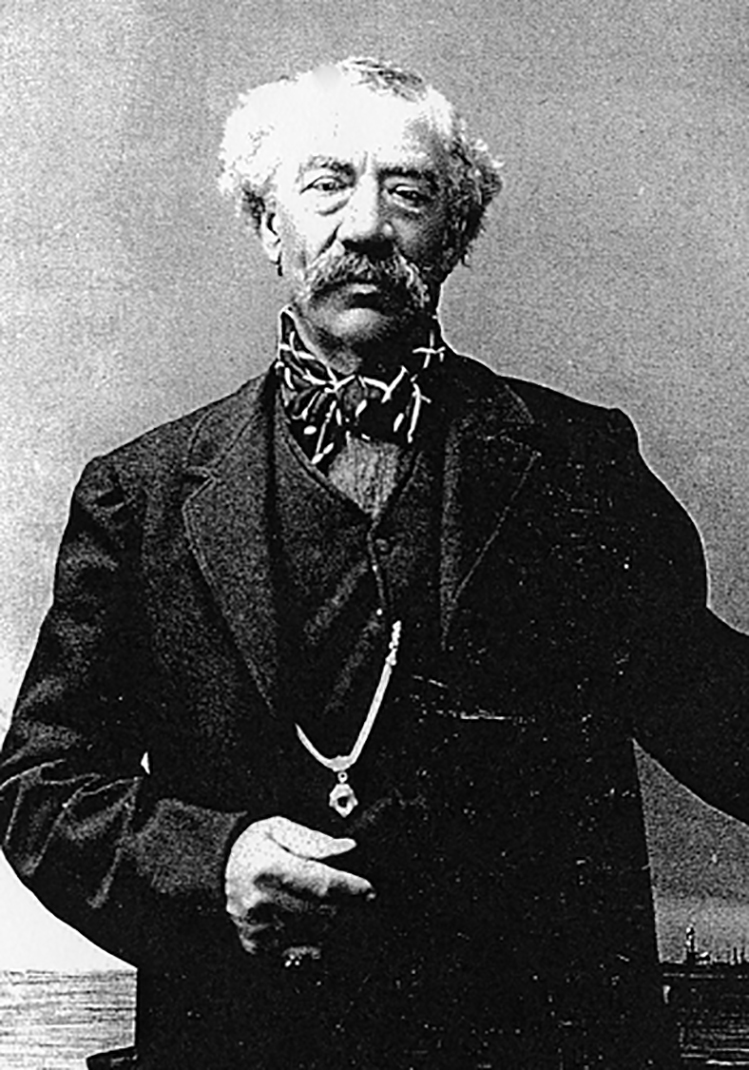

|

| Fred Dupree. |

When Lewis and Clark first passed through this region in 1804 they reported herds of buffalo that stretched across the plains as far as the eye could see. In the 1840s, still, Captain Grant Marsh would tell of having to wait as long as a day while herds crossed the Missouri River in front of his steamboat. This resource, which once seemed limitless, was not. Buffalo fur was in demand back east and in Europe, and buffalo tongues were considered a delicacy. Indian and white hunters harvested animals by the hundreds of thousands, year after year, and the result was predictable.

We can place Fred Dupree at Fort Pierre in 1838, working as an engagee at the trading post owned by Pierre Choteau & Company. Although the trade in buffalo pelts would go on at the post for many years, steadily diminishing numbers of animals meant the peak was past by the time he arrived. A military survey locates Dupree trading buffalo hides at the mouth of the Cheyenne River in 1855, but he was also getting established in the region’s next big business: raising cattle.

Frederick Dupree called many places home during his ranching years, but his main camp was about 35 miles southwest of Eagle Butte, along the Cheyenne River near today’s Carlin Bridge. Frederick and his wife, Mary Ann Good Elk Woman, a Minneconjou, raised 10 children, nine of theirs and a son from her previous marriage. As each of the children married, a small log house with a dirt floor would be built next to the main house.

There were often a dozen or so tipis near the camp, housing the relatives of Mary Ann and others who happened by. Fred was a friendly, sociable sort. Visitors were always welcome at the Dupree camp, and many stayed for several days; they were given food and lodging and friendship.

Dupree spoke French, Lakota and English, sometimes all three in a single sentence. No one is sure if he could read or write, but he managed quite well regardless. At one point the Black Hills Daily Times estimated Fred’s worth at near $1 million, though it allowed this figure could be, “somewhat overstretched.”

Dupree’s generosity and wealth can be gauged from the account of his daughter’s wedding, as reported in a Pierre newspaper: “At age 17, daughter Marcella married Douglas Carlin, a non-Indian who was the issue clerk at the Cheyenne Agency. Their wedding at Cherry Creek on August 27, 1887, was a major social event at the time. The groom was either the grandson or grandnephew of a governor of Illinois Territory and a nephew of a U.S. Army colonel.”

Douglas and Marcella’s wedding was attended by hundreds of Native American and white friends of the family, including members of the Pierre City Council. Both traditional and civic rites were performed. (Marcella’s ceremonial dress can be seen in the Indian Museum of North America, at the Crazy Horse Memorial.) Fred gave the bride and groom 500 head of cattle and 50 ponies to get them started in life, and the celebration was commensurate with such a gift. For most guests the festivities lasted three days. Others lingered for a week or more, consuming two barrels of whiskey and another of wine.

Fred Dupree had been in Dakota nearly 40 years by that time. He had prospered, but Dupree had only to look at Mary Ann’s relatives to see that his affluence came with a price. In years past, the buffalo supported the plains Indians’ very existence, providing them food, clothing and shelter. With the animals fast disappearing, those who depended on them were suffering, and Dupree himself bore some measure of responsibility. His trading company and others had shipped pelts by the million, which encouraged a level of hunting that couldn’t be sustained, and his cattle roamed over the ranges that once were home to vast buffalo herds. Dupree must have realized their extinction was inevitable.

In 1883, Dupree and his ranch hands set out to capture some buffalo on the prairie. Once a small herd was located — reports vary as to the exact location, but it was probably near the Grand River — the party camped nearby. How they managed the capture is unclear. Some accounts say they grabbed the animals as they slept. Others surmise that the hunters built a corral or holding area, drove the animals into it, then cut the ones they wanted away from the rest. However it was done, five buffalo calves were caught. From that modest beginning, the Dupree buffalo “herd” grew to almost 60 head.

Unbeknownst to each other, the man who would carry Dupree’s work forward was already living in the area. James ‘Scotty’ Philip was born in Kansas, one of three brothers, the others being George, a Hays City merchant, and Alex, the foremost cattleman in that state. Scotty left his brothers for Dakota Territory in 1875, drawn by dreams of finding gold in the Black Hills. When that didn’t pan out — Philip was caught by the Army and sent on his way because the Hills were still Indian territory at that time — he started hauling freight and then scouted for General Crook before following his brother into the cattle business. By the turn of the century Philip was a bona fide cattle baron, running 20,000 head on his West River spread.

Philip’s attitude toward the buffalo, like Dupree’s, was influenced by his Lakota wife, Sally. When Frederick Dupree passed away in 1898, Philip bought his buffalo. He placed the animals on a riverside ranch, just north of Fort Pierre, where they thrived. By 1911, when Philip died suddenly, the herd numbered almost 900 animals. No buyer was willing or able to take the whole herd, so it was dispersed. Among the buyers was the state of South Dakota, which placed 36 buffalo in the newly established Custer State Park. That herd, in turn, was used to stock other parks and refuges around the country. When ranchers like Roy Houck got back into the buffalo-raising business during the 1960s, and Ted Turner followed in the 1990s, they did so with animals that descended from Philip’s herd.

Frederick Dupree’s final resting place is much the same as when he arrived. Overhead, the sky goes on forever in every direction; underfoot, the gently rolling hills are covered with a carpet of grass. And thanks to him, there are still buffalo to roam upon it as they did years ago.

Editor’s Note: This story is revised from the January/February 2007 issue of South Dakota Magazine. To order a copy or to subscribe, call (800) 456-5117.

Comments

eventually sold to Scotty Philips with encouragement from Scotty’s

wife (also Lakota) who knew Mary Good Elk Woman Dupree—the

woman who saved the American bison. We live in an interesting culture. One man destroyed and is glorified; one woman saved animals from extinction and is forgotten." My plea is that you remember these fine ladies the next time you write an article about saving the American bison.

Mary Good Elk Woman was the daughter of One Iron Horn and Red Dressing, a very prominent Lakota couple. I am a seventh generation Lakota woman descended from Frederick Dupree and Mary Good Elk Woman through their daughter Marcella who married Douglas Carlin. Marcella and Douglas had their daughter Lillian who married Frank Briggs. Lillian and Frank's daughter Bessie Briggs was my grandmother. Bessie (Bett) married Ernest Smith also a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. Bett and Ernie had five children: Tom, Kathy, Randy, Patty and Terry. I am the daughter of Kathy and Gerald Hopkins.

Word handed down within the family is that Mary Good Elk Woman told Fred Dupree to go get bison calves to save some of the bison herd. She also told him not to come home until he was successful. It took many months for Fred, some of his sons/relatives and some of his friends to track down a herd and then they had to sneak up on the calves and take them from under their mothers' noses.